The development of user-friendly and powerful probabilistic programming libraries (PPLs) has been making Bayesian data analysis easily accessible: PPLs allow a statistician to define a statistical model for their data programatically in either domain-specific or common popular programming languages and provide powerful inference algorithms to sample posterior- and other probability distributions. Under the hood, many PPLs make use of big libraries such as TensorFlow, JAX or Theano / Aesara (a fork of Theano) that provide fast, vectorized array and matrix computations and, for gradient-based inference algorithms, automatic differentiation. In practice, if a user wants to use a PPL, they have to make sure these dependencies (and their dependencies!) are installed, too, which often can be difficult and/or irreproducible: want to compile your compute graph to C code? Then you need a C compiler. But what if you can’t just install the required C compiler version, because there’s already a different, incompatible version on your system? Or you want to run your work code on your private laptop, whose Python version is too low. And so on and so on…

We recently packaged and fixed a couple of PPLs and their related dependencies for use with the Nix package manager. In this blog post, we will showcase Nix and how it gives you easy access to a fully reproducible and isolated development environment in which PPLs and all their dependencies are pre-installed.

A really brief introduction to Nix

Nix assumes a functional approach to package management: building a software component is regarded as a pure, deterministic function that has as inputs the component’s source code, a list of dependencies, possibly a compiler, build instructions, etc. — in short, everything you need to build a software component. This concept is implemented very strictly in Nix. For example, a Python application packaged in Nix has not only its immediate Python dependencies exactly declared (with specific versions and all their dependencies), but also the Python version it is supposed to work with and any system dependencies (think BLAS, OpenCV, C compiler, glibc, …).

Nix and its ecosystem is an extremely large and active open source project, as indicated by the Nix package collection containing build instructions for over 80,000 packages.

All these packages can be made available to developers in completely reproducible shells that are guaranteed to provide exactly the same software environment on your laptop, your AWS virtual machine or your continous integration (CI) runner.

A limitation of Nix is that it runs only on Linux-like systems and that it requires sudo privileges for installation.

You can also use Nix in Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) and on MacOS, but support for the latter is not as good as for standard Linux systems.

After you installed Nix, you can get a shell in which, for example, Python 3.9, numpy, and OpenCV are available simply by typing:

$ nix-shell -p python39Packages.numpy open-cvYou can now check where this software is stored:

$ python -c "import numpy; print(numpy.__file__)"

/nix/store/bhs02rwyhgsdwriw9f1amkx9020zpir5-python3.9-numpy-1.21.2/lib/python3.9/site-packages/numpy/__init__.py

$ which opencv_version

/nix/store/hyni6hs71dphfy2s5yk8w1h3gzh90a44-opencv-4.5.4/bin/opencv_versionYou see that all software provided by Nix is stored in a single directory (the “Nix store”) and is identified by a unique hash.

This feature allows you to have several versions of the same software installed side-by-side, without the risk of collision and without any modification to the state of your system:

want Python 3.8 and Python 3.9 available in the same shell?

Sure, just punch in a nix-shell -p python38 python39!

Example: reproducible development Nix shell with PyMC3

Now that we hopefully made you curious about Nix, let’s finally mix Nix and probabilistic programming. As mentioned in the introduction, we made a couple of probabilistic programming-related libraries available in the Nix package collection. More specifically, we fixed and updated the packaging of PyMC3 and TensorFlow Probability and newly packaged the Theano fork Aesara, which is a crucial dependency for the upcoming PyMC 4 release.

To get a Nix shell that makes, for example, PyMC3 available, you could just run nix-shell -p python39Packages.pymc3, but if you want to add more packages and later recreate this environment, you want to have some permanent definition of your Nix shell.

To achieve this, you can write a small file shell.nix in the functional Nix language declaring these dependencies.

The shell.nix file essentially describes a function that takes a certain Nix package collection as an input and returns a Nix development shell.

An example could look as follows:

let

# use a specific (although arbitrarily chosen) version of the Nix package collection

default_pkgs = fetchTarball {

url = "http://github.com/NixOS/nixpkgs/archive/nixpkgs-unstable.tar.gz";

# the sha256 makes sure that the downloaded archive really is what it was when this

# file was written

sha256 = "0x5j9q1vi00c6kavnjlrwl3yy1xs60c34pkygm49dld2sgws7n0a";

};

# function header: we take one argument "pkgs" with a default defined above

in { pkgs ? import default_pkgs { } }:

with pkgs;

let

# we create a Python bundle containing Python 3.9 and a few packages

pythonBundle =

python39.withPackages (ps: with ps; [ pymc3 matplotlib numpy ipython ]);

# this is what the function returns: the result of a mkShell call with a buildInputs

# argument that specifies all software to be made available in the shell

in mkShell { buildInputs = [ pythonBundle ]; }You can then enter the Nix shell defined by this file by simply typing nix-shell in the file’s directory.

When doing that for the first time, Nix will download all necessary dependencies from a cache server and perhaps rebuild some dependencies from scratch, which might take a minute.

But once all dependencies are built or downloaded, they will be cached in the /nix/store/ directory and available instantaneously for later nix-shell calls.

Now let’s see what we can do with our Nix shell! We first check where Python and PyMC3 are from and then run a small Python script that does a Bayesian linear regression on made-up sample data:

$ nix-shell

[... lots of output about downloading dependencies]

[nix-shell:~/some/dir:]$ which python

/nix/store/rhc1yh5dvhll2db9n8qywpg6ysdv6yif-python3-3.9.10-env/bin/python

# *Not* your system Python, but a Python from your Nix store

[nix-shell:~/some/dir:]$ python -c "import pymc3; print(pymc3.__file___)"

/nix/store/rhc1yh5dvhll2db9n8qywpg6ysdv6yif-python3-3.9.10-env/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pymc3/__init__.py

# PyMC3 is in your Nix store, too. The state of your system Python installation is unchanged

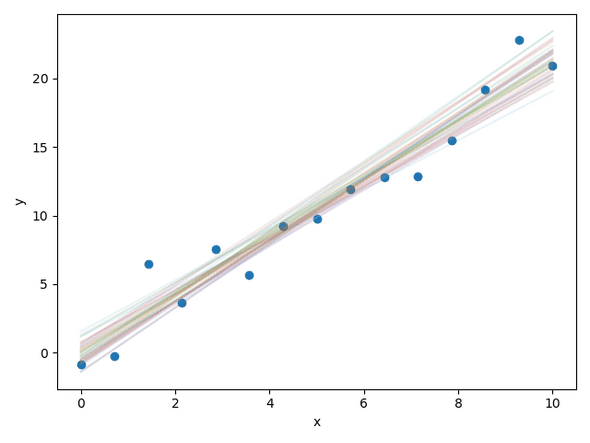

[nix-shell:~/some/dir:]$ python pymc3_linear_regression.py

Auto-assigning NUTS sampler...

Initializing NUTS using jitter+adapt_diag...

Multiprocess sampling (4 chains in 4 jobs)

NUTS: [noise, intercept, slope]

Sampling 4 chains for 1_000 tune and 1_000 draw iterations (4_000 + 4_000 draws total) took 5 seconds.[nix-shell:~/some/dir:]$ exit

# now you're back to your normal shell...

$ which python

/usr/bin/python

# and back to your system PythonAs you can see, you entered an isolated development shell that provides the dependencies you specified and that allows you to run PyMC3 without changing the state of your system Python installation.

And if you now run the same sequence of commands on a different machine with Nix installed, it will just work just the same way as above!

Just put the shell.nix file in the same VCS repository as your code and voilà - you’re sharing not only your code, but also the software environment it was developed in.

This is not specific to PyMC3 at all: a reproducible and isolated software environment containing TensorFlow Probability or Aesara can be defined and used similarly; just replace pymc3 by tensorflow-probability or aesara in your Python bundle.

On the face of it, that all might seem not so different from a Python virtual environment. But we saw the crucial difference above: Python virtual environments manage only Python dependencies, but no dependencies further down the “dependency tree”. Nix, on the other hand, behaves thus rather a bit like Conda or, although it’s quite a stretch, like a Docker image: it provides system dependencies, too. A detailed comparison of these alternatives to Nix is beyond the scope of this post, though.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we gave a short introduction to the Nix package manager and its development shell feature and demonstrated how to use it to obtain a reproducible software environment that contains PyMC3 and a few other Python dependencies.

We also showed that these software environments don’t mess with your system state and thus allow you to fearlessly experiment and try out new software without breaking anything.

In this regard, Nix provides an alternative to Docker or Conda, but it can do much, much more — in fact, there is even a whole Linux distribution (NixOS) that is based on the Nix package manager!

You can find the shell.nix file and the PyMC3 example script in Tweag’s blog post resources repository.

If you would like to learn more about Nix, visit the Nix website for more resources, browse the Nix Discourse or pop in to #nix:nixos.org on Matrix or #nixos on the Libera.Chat IRC network.